A couple months ago, friends and business contacts started asking me for a crash course on my professional research studying virtual environments. Their interest reflects an explosion—which you’ve probably noticed—of noise and hype surrounding something called the “metaverse.”

This article is an introduction for a complete or almost beginner. There’s plenty of mainstream coverage on the topic, but it often conflates concepts: virtual reality is not the metaverse (though it’s related), and crypto/Web3 by itself is not the metaverse (though also related). Confusing, I know. Whether you’re a businessperson or bystander, this is my best effort to lay everything out.

What Is the Metaverse?

In 99.99% of cases, provided the term is used correctly, you could replace the word “metaverse” with “internet” and the sentence will mean the same thing. So why is everyone using this fancy new word? I think analyst Doug Thompsonsaid it very well when he noted that “we’re using the term as a proxy for a sense that everything is about to change.”

So if the metaverse is just the internet—what about the internet is about to change? To answer that question, I’ve broken this article into four parts:

- Spatial Computing (What is that?)

- Game Engines (What are those?)

- Virtual Environments (Is that the metaverse? …sort of)

- Virtual Economies (Please don’t tell me I have to learn about NFTs…you might)

For those that want my definition of the metaverse up front, I’d say: The metaverse is the internet, but it’s also a spatial (and often 3D), game-engine-driven collection of virtual environments. There is a lot missing from this definition (like avatars), but if you’re like many people, that will already sound like a made-up buzzword salad.

Let’s explore.

1. Spatial Computing (and the History of the Interface)

To understand the changes coming to life online, you have to start with the seemingly obvious way we currently access the internet: computers.

And to understand where we’re headed, you have to look at the history of computer interfaces. By computer interface, I’m referring to the way that humans interact with digital machines to get them to do what we want.

We take for granted how easy and intuitive working with computers has become in our lifetimes, but it wasn’t always so easy.

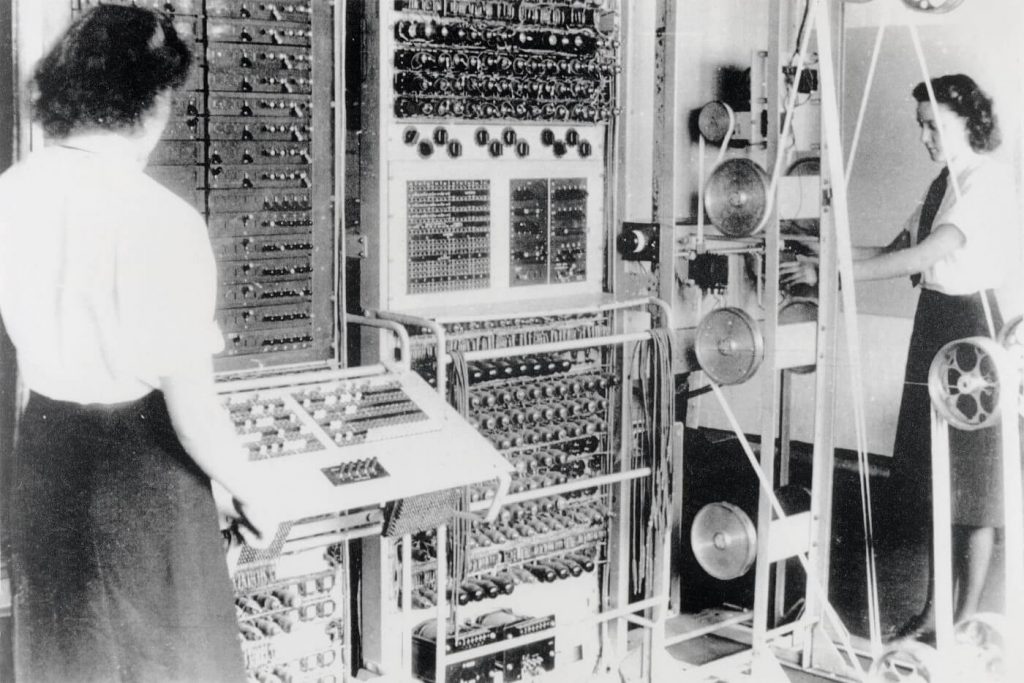

In the middle of the 20th century, the “programming language” engineers used to get a computer to do things involved sticking their hands into the actual machines to wire cables. (Also, most early computer programmers were women.)

Then engineers invented a new interface using punch cards, which allowed us to keep our hands to ourselves.

After punch cards came command lines (like MS-DOS), which were a breakthrough because you could interact by typing words. But the real mainstream moment for computers was the invention of the graphical user interface (GUI). This is when working with computers came to involve clicking pictures and is what most of us take for granted as “just how they work today.” GUIs are now used in everything from ATMs to ticketing machines, and they’re the reason ordinary, non-programmer people like us can use them.

Why go through this history?

The point is that at every stage in the development just described, working with computers became easier, more accessible, and more people could use them.

Clay Bavor, at Google, whose description of this history and insights I am borrowing here, puts it this way:

“Over the past several decades, every time people made computers work more like we do—every time we removed a layer of abstraction between us and them—computers became more broadly accessible, useful, and valuable to us. We, in turn, became more capable and productive.

Today, the next great computing interface is emerging—it just doesn’t have a good name yet. You may have heard about concepts like augmented reality, virtual reality, mixed reality, immersive computing, or whatever two-letter acronym.

What all of these concepts share is that they involve the use of three-dimensional space. That is a very big deal.

My colleague at Singularity University, interface designer Jody Medich, taught me just how important 3D space is for the human brain. Which makes sense. We are born into 3D space. We grow up living in 3D space. It would make sense that our brains and bodies are built to interact in 3D space.

So this term “spatial computing” is becoming a commonly used way to refer to these interfaces. Be careful not to conflate this with the metaverse, since many spatial computing people don’t consider themselves to be involved with, or a part of, all this metaverse nonsense. But it is related, and we’ll come to that.

One other way to think of this is to consider why we don’t typically see grandparents playing video game consoles. It takes time to develop the motor skills to smash buttons on a controller in the right way. Similarly, we take for granted that at some point we had to learn the motor skills to type.

We do, however, see more grandparents playing systems like the Nintendo Wii. You pick up a controller and swing your arms. Intuitive, easy, and anyone can do it. That’s a spatial interface. The big deal is that more people, including many more grandparents, could become comfortable using computers.

Generally, you should also think of spatial things as having the properties of moving around in space. In this sense, though not controlled using a spatial interface, a traditional video game like Fortnite is spatial (you move around), whereas a Zoom call is not. I don’t want to complicate things, but spatial audiois another thing too.

To explain why this matters, I often use the example of Protectwise (now a Verizon company). They build tools to help cybersecurity professionals detect threats to their computer systems. Typically, a cybersecurity person lives life inside dashboards looking at log files to sense what’s happening. What if that data could be turned into a spatial environment? Now patrolling your company’s computer system is like playing a video game. More people could do that since it’s more intuitive. Take a look:

Spatial computing like this is coming to life online.

2. Game Engines: Construction Tools to Build the Metaverse

Game engines may be one of the most consequential technologies of the next decade. I know that might sound a little crazy. But hear me out.

A game engine is the software tool developers use to build (and run) video games. In these software programs you can upload 3D objects, apply rules for how those objects can move, add sounds, etc. The Protectwise thing shown above was made using the Unity game engine.

In business, the term “video game” is also misleading, since it suggests something recreational or non-serious. But as the world becomes more digital, game engines are powering the computing interfaces for all sorts of industries.

Aaron Lewis nicely points out, “…game engines are basically eating the world. Urban planning, architecture, automotive engineering firms, live music and events, filmmaking, etc. have all shifted a lot of their workflows/design processes to Unreal Engine and Unity.”

Take the new electric Hummer as an example; the first car to have an Unreal-Engine-based interface. The vehicle takes information from its sensors and visualizes it in 3D on the dashboard. This is spatial computing in the real world.

Another jargon-y term you might start to hear is “digital twin,” which is the idea that physical things (like a Hummer) can use its sensor data to create a software copy of itself inside a computer. This lets humans interact with simulated industrial objects as if they’re computers.

A famous example is Hong Kong International Airport’s Terminal 1 which uses a digital twin in the Unity game engine to give facilities managers a real-time view of passenger activity and equipment that might need repairs. Think of it like the terminal’s 3D selfie.

While there’s more happening in the world of game engines than I can go into, there are two engines to know: Unreal and Unity. Unreal is owned by Epic Games, the publisher who owns Fortnite, and Unity is a large publicly traded company. (Personally, I’ve only ever used Unity since it’s designed to be somewhat beginner-friendly.)

The last thing you should know about game engines is that they are going to see mind-bending levels of improvement this decade. You might not have seen the internet lose its collective mind over the demo release of the newest Unreal Engine 5, but everyone went nuts. For an approachable summary of why it’s a big deal, Estella Tse gave me a really clear explanation.

And if you have 20 minutes to spare, my classmate sent me this, and it blew my mind:

The takeaway is that this decade, graphics will stop looking like “graphics.” The limit for how high game resolution can be is falling away, and we’ll see photorealistic virtual environments that look like real life. This means you should try to see past the cartoonish aesthetic today’s metaverse coverage will put in your mind.

For example, imagine what that means for something like Beyond Sports, a Dutch company that uses Unity and real-time positional data taken from sports to render live events as they are happening inside virtual reality. Picture this in 10 years—walking around inside a game live with your friends—and now we’re approaching what we might be doing in the metaverse.

And here we can introduce the first part of a good definition of what the term metaverse is pointing toward:

If you start paying attention to it, you’ll notice game engines everywhere, which is especially true for…….

3. Virtual Environments

Now that we’ve introduced spatial computing and game engines, we’ve arrived where most mainstream coverage of the metaverse picks as its starting point.

Virtual environments are the “places” we’ll be logging into in tomorrow’s internet. They are also a tricky thing to define. In many ways, Twitter and Discord (an online messaging platform) are already virtual environments where people meet and exchange messages and information.

The virtual environments I’m exploring here, however, are the spatial ones built in game engines, and there are two kinds to explore. First is real-world augmented reality (think Pokémon Go).

The other is the more traditional online or purely digital virtual environments you have to sit down at a computer (or put on a VR headset) to access, though this distinction is arbitrary and already falling away.

Pokémon Go is a helpful example of AR in the real world. It’s a spatial game, built using Unity, that overlays 3D characters on the physical world. Does that mean we can consider Pokémon Go to be part of the metaverse? Well yeah, sort of I guess, sure, who’s to say (I guess I’m saying). The current definition is slippery. We’re still in the “define your terms” stage, so be careful of that in the media.

In the future, it won’t just be games—the entire physical world will be like a canvas we can paint with data.

To make this all happen, technology companies are scrambling to build what’s referred to as the mirrorworld or AR cloud. These words mean the same thing as “digital twin” from earlier. Just extend the airport terminal concept to the entire Earth, and you have a tool to build virtual stuff on top of our everyday world. If you want to go deeper on this, I wrote this article exploring its impact on society.

This is all another way of saying the internet is spilling out of our phones and computers and merging with physical reality—and it’s why that Hummer might be part of the metaverse. See, for example, how Niantic (the company who publishes Pokémon Go), market their technology to developers.

So, the metaverse won’t just be random cartoon game worlds built by developers. It will also be digital replicas of very real spaces, likely the whole planet, and digital twins of industrial stuff like your car. It will eventually come to include sitting in your backyard with family members beamed in as avatars or putting on a VR headset to walk around other cities in real time.

Next, let’s explore more traditional virtual worlds. Perhaps the most well-known example is a platform called Second Life, which was a huge phenomenon roughly 15 years ago and is still big today.

If you’re not familiar, Second Life is a collection of virtual worlds built by users that you can explore as an avatar. Millions of users signed up, and lots of stuff happens there. It’s also a good reminder that anytime you see the media claim that something is “the first” virtual-based whatever, that’s very likely not true.

A very real economy exists in Second Life, where users buy and sell virtual goods and services, and it has its own currency; the Linden Dollar.

Today, there’s a whole suite of platforms that could be thought of as successors to Second Life. One of these, Rec Room, just raised $145 million at a $3.5 billion valuation; this stuff is getting serious. Other platforms include VRChat, Altspace, Decentraland, and Somnium Space, among many others.

Another trendy thing to do in metaverse-speak is talk about how games like Fortnite and Roblox are fledgling metaverse experiences (which is true). On the surface, they come masked as games, but underneath they are spatial environments where people meet up and increasingly go to Travis Scott or Lil Nas X concerts.

The ultimate vision of the metaverse is that all of these experiences (Beyond Sports, Pokémon Go, Fortnite, Roblox) will become an interconnected network of virtual environments—in other words, the internet, but for experiencing stuff.

My own journey into all this started several years ago on a platform called Sansar, originally launched by the same company behind Second Life. Here, my friend Sam is showing me around a space built by one of their users; Fnatic (one of the biggest eSports teams in the world). I’m in a VR headset at home in San Francisco while Sam is in Los Angeles:

What struck me is that I was “walking around” with Sam inside the internet. Also, here was a retail e-commerce site to buy clothes online. Just like the world wide web must have struck CEOs in the mid-90s as an oddity that may (or may not) be relevant for their business, today’s CEOs are probably scratching their heads observing all this metaverse noise.

I will say that just as most companies today have a website, at some point most companies will have a 3D virtual environment of some kind.

With spatial computing, game engines, and virtual environments like these, we’re closing the gap between experiences you have in real life (going to a concert, hanging out with friends, etc.) and experiences mediated by a computer online. This is what concepts like Ready Player One (a book by Ernest Cline adapted into a film by Steven Spielberg) are pointing toward.

And here we get our next helpful description of the metaverse:

To tie it all back together the metaverse is the internet, but also a spatial (and often 3D), game-engine-driven collection of virtual environments.

And just as today’s internet has absorbed vast portions of our economic activity, tomorrow’s metaverse will consist of massive…oh no, please not NFTs…here it comes…

4. Virtual Economies (…and NFTs)

One of my favorite statistics is that Second Life still supports an annual economy worth roughly $500 million (that number has grown during the pandemic). The GDP of Second Life is larger than the economies of some real-world countries.

Fortnite, a game that doesn’t cost a penny to play, still earned $9 billion in 2018 and 2019. How? They sell in-game stuff for players to express themselves in a variety of ways including virtual clothing, dance moves, and other items. In some ways the metaverse is just a giant virtual fashion industry.

If that sounds silly or weird, just think about how someone carefully plans what clothes to wear or what profile picture to use on LinkedIn. We care about how we express ourselves in the world. If we’re going to spend an increased portion of our time online, it’s not so silly to expect people will want to buy expensive Gucci bags to carry around Roblox.

So where do NFTs fit into all of this? Among other uses, NFTs offer the infrastructure to let people take custody of this virtual stuff.

I hate to do this, but it’s worth taking one giant step back to unpack what an NFT actually is.

The first thing to note is that NFTs run on blockchains. A blockchain is really just a fancy Excel spreadsheet that keeps track of who owns what (like what a bank does to keep track of who owns what money). Today, we rely on centralized authorities like banks to keep track of how much money is in which accounts as cash is shuffled between people and businesses. The idea behind a blockchain is that everyone just gets a copy of the same spreadsheet, and the big deal/breakthrough is that through complicated cryptography (which is where the “crypto” in cryptocurrency comes from) all those spreadsheets communicate and agree about which transactions are legitimate.

No more needing central trusted authorities. No way to hack, change, or mess around with what the spreadsheet says.

NFT stands for non-fungible token. The key word is ‘fungible’ which just means you can exchange something for an equivalent version, and it will be equally valuable (bitcoin is fungible because it doesn’t matter which bitcoin you have— they are all equally valuable). Non-fungible is the opposite: each item is unique. This is why we’re seeing a lot of digital art being bought and sold using NFTs. NFTs use blockchains to determine who owns what.

This shift toward a decentralized way of managing life online is called Web3 (a word you’ll hear more and more and is worth getting to know).

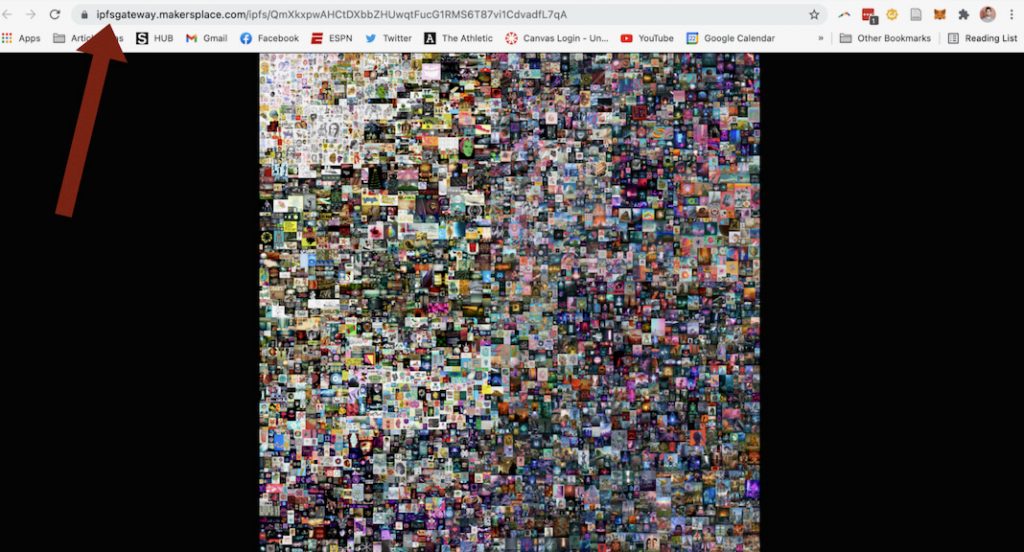

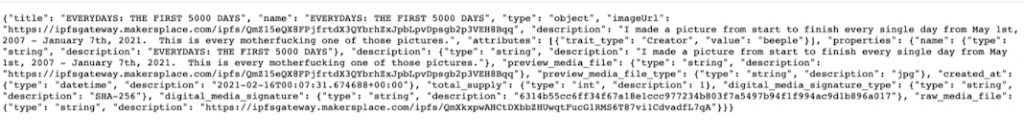

Let’s use a real example. Maybe you saw the front page of The Wall Street Journal this summer when an NFT for a digital image sold for $69 million.

Let me save you $69 million and share the link where that image’s file lives online. You can save it to your computer, and now you also own the file. Right? Well, kind of, but not in the sense everyone cares about.

Most media coverage doesn’t explain this, but most NFTs are not the thing itself; in this case the JPEG file. The NFT is the token associated with the metadata that points at the thing. Here’s the metadata for that NFT, by the way. There is something called an “on-chain NFT,” but we won’t go there.

The reason NFTs and the metaverse are conflated so often is that there’s an expectation that they may power these virtual economies by acting as the infrastructure mediating the exchange of information and assets online.

To be clear, this is not yet a universally agreed upon idea. Second Life, Fortnite, and plenty of other platforms have been doing just fine without NFTs. But one reason NFT/crypto is one of the noisiest places on the internet is because it’s fast-paced, novel, and supported by an absurd amount of money.

I don’t mean that in a negative way; but this area is the unmapped, build-it-as-we-go, unsettled frontier of life online. There are some fascinating projects at the front end of this, but whether NFTs do or don’t power some dematerialized system of capitalism misses the point that NFTs are likely more important than just “owning stuff.”

Now we can tie together everything we’ve learned about the metaverse and review a recent scene from an online event to explore the way NFTs might play a role.

Here is the ‘Metaverse Festival’ (yes, a real thing) that was headlined by performances from global stars like Deadmau5. It happened in the browser-based Decentraland (a spatial, game-engine-driven, virtual environment).

It’s Friday night, and you head to the nightlife district of Decentraland (a plot of land which is an NFT). To get in you must be of age. You carry an identity token (which could be an NFT), to verify your eligibility for entrance.

You notice someone wearing a hoodie (an NFT) from RTFKT, a virtual apparel company recently acquired by Nike. Those are expensive, I’m told.

It’s free to enter, because the event is sponsored by Kraken, who wants to be the cryptobank of the metaverse. By attending, you’re issued what’s called a “proof of attendance protocol” token, or POAP (that is an NFT).

Later, when you sign up at Kraken, they offer a discount to those who can show, with that token, they attended the event.

Metaverse or no metaverse, as John Palmer explains, NFTs mean the internet becomes a place where everyone has an inventory. Earlier we mentioned the metaverse is an interconnected collection of experiences, and if that’s the case, you might want to carry your single identity, history, and inventory of assets around with you. If that sounds familiar it’s basically giving users back their own cookies and personal data from big companies. I don’t want to go there; but it’s why a lot of people are worried about Facebook/Meta building a centralized metaverse instead of one that is open and decentralized.

I’ve gone way down an NFT rabbit hole here, but it’s worth stitching together the spatial computing/virtual world developments with what’s been happening in crypto/Web3. When I started this research seven-ish years ago, crypto people were far away and somewhere else. Today, I now have to explore Web3 stuff too, since these areas are merging.

. . .

If you’re still here—thank you—you might still be wondering: So, what? How does any of this meaningfully improve anything about the world, or even the internet? How is any of this better than what we have today? Honestly, fair point.

Lots of people will have points of view, and I won’t advocate one perspective or another. But I do have a personal anecdote.

At the start of my MBA program, the UK government had implemented a rule that no more than six people could be together indoors. For 300 ‘zero-chill/connect on LinkedIn’ business students, that’s a tough start to the year.

We even tried a full Zoom call with all of us.

My classmates will remember me as that kid who threw some weird internet house party using a platform called High Fidelity. It employs spatial audio, so you only hear the people clumped around you. It took some getting used to but was a reasonable way to get 150 of us, as basic 2D avatars, moving around in a shared online space.

What the metaverse enables, through dimensional space, is a way to replicate some but not all natural human behaviors, which you can’t replicate in existing online spaces such as Slack, Discord, or Zoom. There are times you want the magical chaos of unplanned social interaction mediated by “personal space.”

In the professional world, I’m endlessly fascinated by this company which runsa 60,000-person organization from inside a virtual world built in Unity. The founder of that software company tells me that when you have to actually walk your avatar from meeting to meeting, there’s opportunities for chance encounters you’d never get jumping from Zoom to Zoom.

I’ve also used that same software to run learning programs, and likewise, there are “moving around the room” type learning activities I could never run using Zoom.

Additionally, the metaverse might grow to become a more intuitive internet. Just like spatial computing interfaces are easier to use, websites may become like walking into physical stores, something our brains and bodies might better understand.

But it goes without saying, we won’t replace real-world experiences nor should we want to. We also won’t stop using today’s platforms, like video-conferencing. The metaverse is just the evolutionary next stage of the internet, and offers a new suite of communication tools that will be more helpful for some things and less for others.

To conclude: this is all a long-winded way of saying the metaverse is the internet. But spatial. And built with game engines. And probably NFTs. And who knows where that takes us…

This article is republished with permission from the author’s Medium page. Read the original article.

Image Credit: The first selfie the author ever took as an avatar.

Looking for ways to stay ahead of the pace of change? Rethink what’s possible. Join a highly curated, exclusive cohort of 80 executives for Singularity’s flagship Executive Program (EP), a five-day, fully immersive leadership transformation program that disrupts existing ways of thinking. Discover a new mindset, toolset and network of fellow futurists committed to finding solutions to the fast pace of change in the world. Click here to learn more and apply today!

Author:

Aaron Frank is a writer and speaker and one of the earliest hires at Singularity University. Aaron is focused on the intersection of emerging technologies and accelerating change and is fascinated by the impact that both will have on business, society, and culture.

As a writer, his articles have appeared online in Vice’s Motherboard, Wired UK and Forbes. As a speaker, Aaron has lectured fo… Learn More